It is hot in Addis Ababa. Already crowds are beginning to gather in the historic Ethiopian capital, waiting under the bright, clear skies, men and women dressed in the traditional white shamma, their children playing beneath banners of red, green, and yellow—the colours of the Ethiopian flag. In the grassy fields of Jan Meda, to the northeast of the city centre, large tents have been erected and hundreds of locals and tourists swarm the area, anxious to catch a glimpse of the coming procession. It is January 19th, Ketera, the first day of Ethiopia’s three day celebration of the Epiphany, and the atmosphere is electric.

Every year, pilgrims from all over the country flood the city to take part in the greatest, most colourful festival on the Orthodox Christian calendar. Timkat, the celebration of the baptism of Jesus Christ in the River Jordan, is observed in other parts of the country as well, but no festival is as vibrant nor as widely attended as the one in Addis. The festival itself dates back to the 16th century, but was considered a private, holy experience, marked only by churches and monasteries until the baptismal ceremonies were introduced. These days, joyous crowds—often numbering in the thousands—gather all over Northern Ethiopia to witness the priests carrying the Tabot (a model of the Ark of the Covenant) from their churches, parading them through the city until they reach their chosen destination.

The Cradle of Christianity

More than 40% of Ethiopia’s 94 million population is Christian, and the majority of those belong to the Orthodox Church. For them, Timkat (also spelled Timket and Timqat), Amharic for ‘baptism’, is one of the most important occasions of the year. Christianity in Ethiopia dates back to the 1st Century AD, and the country is considered by scholars to be the first nation in the world to embrace the religion. While pious travellers may find Ethiopian tours particularly meaningful, it is impossible not to feel moved by the nation’s ecstatic, reverent devotion, rooted as it is in such ancient tradition.

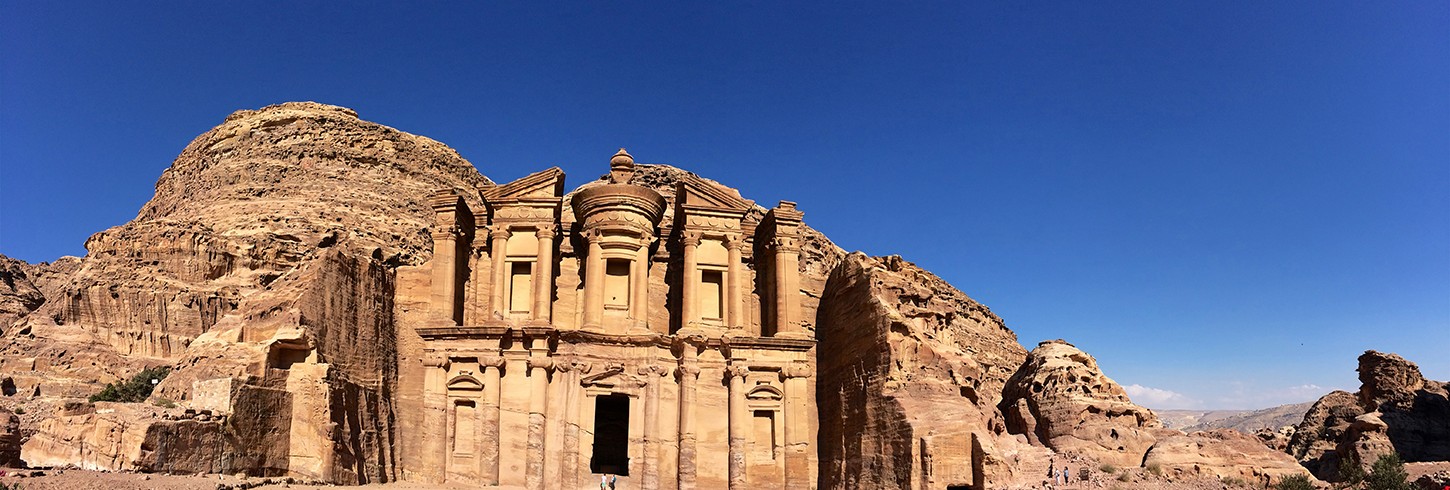

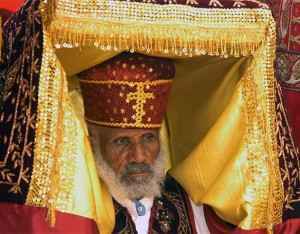

Priest carryingthe Tabot Priests join the procession

Processions and Vigil

A priest, garbed in brightly coloured robes embellished with intricate gold designs, swings an elaborate censer before him, bathing the crowd in a fog of thick incense. Other priests carry ornate ceremonial umbrellas and staffs capped with the Ethiopian cross, which they beat against the road as the pass by. The procession is solemn yet joyous, accompanied by a swell of voices lifted in song. At the front, priests carry the shrouded Tabots over their heads, cloaked in dazzling embroidered fabrics. Ordinarily, the Tabots are not seen by the public, and it is the Tabot (rather than the church building) that is consecrated, marking it as an exceptionally holy relic. The effect is breathtaking, and members of the crowd break from the pack to join the parade as it continues toward Jan Meda, where the blessing will take place.

Baptism

When they reach water, vigil is held over the Tabots, and onlookers enjoy picnics under the star-studded sky, by the light of oil lamps. At 2:00am, the clergy perform mass and the crowd celebrates the Divine Liturgy. The mood is one of unbridled joy and serenity: the sense of gratitude and exhilaration is so palpable that you feel it in your bones, something old and mystical that seems to sing through your veins. Towards dawn, the priest takes his ceremonial cross and snuffs a candle burning on a pole set in a nearby river. Then, the water is blessed, just as John the Baptist blessed the River Jordan for Jesus Christ. Water is taken and sprinkled onto participants and onlookers, reconfirming their devotion to their faith. The mood is jubilant, building to crescendo, and the crowd surges forward. Many in the congregation throw themselves into the river, still fully clothed in their traditional shamma, immersing themselves completely in the consecrated water. The crowd bellows and whistles as more and more bodies break the cold surface of the river, applauding this supreme expression of spiritual love. Small injuries are not uncommon as bodies batter against the unforgiving water, slipping and sliding against ancient stone—but the pilgrims do not appear perturbed. They luxuriate in the holy water, splashing themselves and one another, navigating the river in broad strokes as their sins are washed away.

A priest sprays holy water into the crowd The joyous crowdre-enact their Baptism

The Feast of St Michael the Archangel

By noon, the crowd has shown no sign of dissipating; many have stayed all day to participate in the festivities, and those who returned home after the morning blessing are now back to help escort the Tabot home to its resting place in the church. The procession is merry, crackling with joyful energy, as young men wheel about in celebratory dance, the priests chanting traditional songs and hymns.

As the afternoon winds down, onlookers return home to prepare for the feast of Michael the Archangel, perhaps the most popular saint in Ethiopia. But within the hallowed walls of Addis Ababa’s numerous churches, it is a different, more somber scene. There, worshippers congregate in the church grounds to listen in on a final service, and once the closing prayer is uttered, the Tabot disappears inside once more, gone and guarded for another year, until next Timkat.